|

| April 23, 2019 | Volume 15 Issue 16 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

Neat! Laser pointer attacks on aircraft could be deflected by liquid crystals in windscreens

Aiming a laser beam at an aircraft isn't a harmless prank: The sudden flash of bright light can incapacitate the pilot, risking the lives of passengers and crew. But because attacks can happen with different color lasers, such as red, green, or even blue, scientists have had a difficult time developing a single method to impede all wavelengths of laser light. Recently, researchers described a solution where liquid crystals incorporated into aircraft windshields can block any color of bright, focused light.

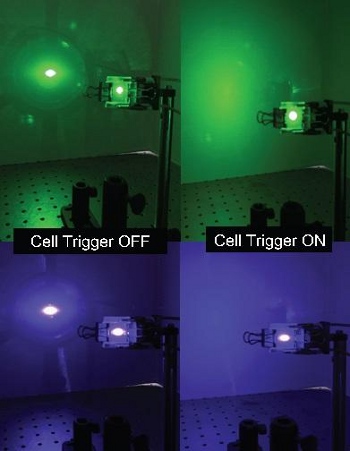

Liquid crystals sandwiched between two1-inch squares of glass scatter green and blue light on a wall when the cells are triggered by laser illumination (right panels). [Credit: Daniel Maurer]

The researchers presented their results March 31 at the American Chemical Society (ACS) Spring 2019 National Meeting & Exposition, which featured nearly 13,000 presentations on a wide range of science topics.

According to the Federal Aviation Administration, 6,754 laser strikes on aircraft were reported in 2017.

"We were approached by collaborators in the aviation department at our university about the growing problem happening at airports across the world, where people were shooting lasers at planes during takeoff and landing, the critical phases of flight," says Jason Keleher, Ph.D., Lewis University. Keleher is the project's principal investigator. Such attacks, which cause bright flashes of light in the cockpit, can distract pilots or inflict temporary or permanent visual damage, depending on the wavelength and intensity of the laser.

"We wanted to come up with a solution that didn't require us to completely re-engineer an aircraft's windshield, but instead adds a layer to the glass that harnesses the existing power system for windshield defrosting," says Daniel Maurer, an undergraduate student also at Lewis University.

Rather than being integrated into the windshield, previous approaches have included pull-down windscreens or goggles that pilots don during takeoff and landing. However, these can be inconvenient, because they require the flight crew to take these precautions whether or not they are actually being targeted. An even bigger problem is that these strategies work only for specific wavelengths of laser light. "They don't block everything," Maurer says. "They're usually targeted toward green lasers, because those are used for the majority of the attacks."

To develop their new approach, the researchers took advantage of liquid crystals -- materials with properties between those of liquids and solid crystals that make them useful in electronic displays. The team placed a solution of liquid crystals called N-(4-methoxybenzylidene)-4-butylaniline (MBBA) between two 1-in.-sq panes of glass. MBBA has a transparent liquid phase and an opaque crystalline phase that scatters light. By applying a voltage to the apparatus, the researchers caused the crystals to align with the electrical field and undergo a phase change to the more solid crystalline state.

The aligned crystals blocked up to 95 percent of red, blue, and green beams, through a combination of light scattering, absorption of the laser's energy, and cross-polarization. The liquid crystals could block lasers of different powers, simulating various distances of illumination, as well as light shone at different angles onto the glass.

In addition, the system was fully automatic: A photoresistor detected laser light and then triggered the power system to apply the voltage. When the beam was removed, the system turned off the power, and the liquid crystals returned to their transparent, liquid state. "We only want to block the spot where the laser is hitting the windshield and then have it quickly go back to normal after the laser is gone," Keleher says. The rest of the windshield, which was not hit by the laser, would remain transparent at all times.

Now that the researchers have shown that their approach works, they plan to scale it up from 1-in. squares to the size of an entire aircraft windshield. Initial results have shown that a sensor grid pattern on 2-in. squares of glass will respond only to the section of glass that is illuminated. The team is also testing different types of liquid crystals to find even more efficient and versatile ones that return to the transparent state more quickly once the laser is removed.

Source: American Chemical Society

Published April 2019

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy